“We’re going to ignore the giraffes on the right,” Frances yelled over the roaring engines as we sped along the path at 40 clicks per hour. The heat poured down from the Northern Serengeti’s mid-day sun.

Later our guide confessed, “This wildebeest migration is a crazy business. You can approach it one of two ways. You can sit and patiently wait for them to cross, or you can rush from one point to the next and hope to be there at the right time.”

“Today, we raced, and we missed them,” Frances apologized. “Tomorrow, we’ll wait.”

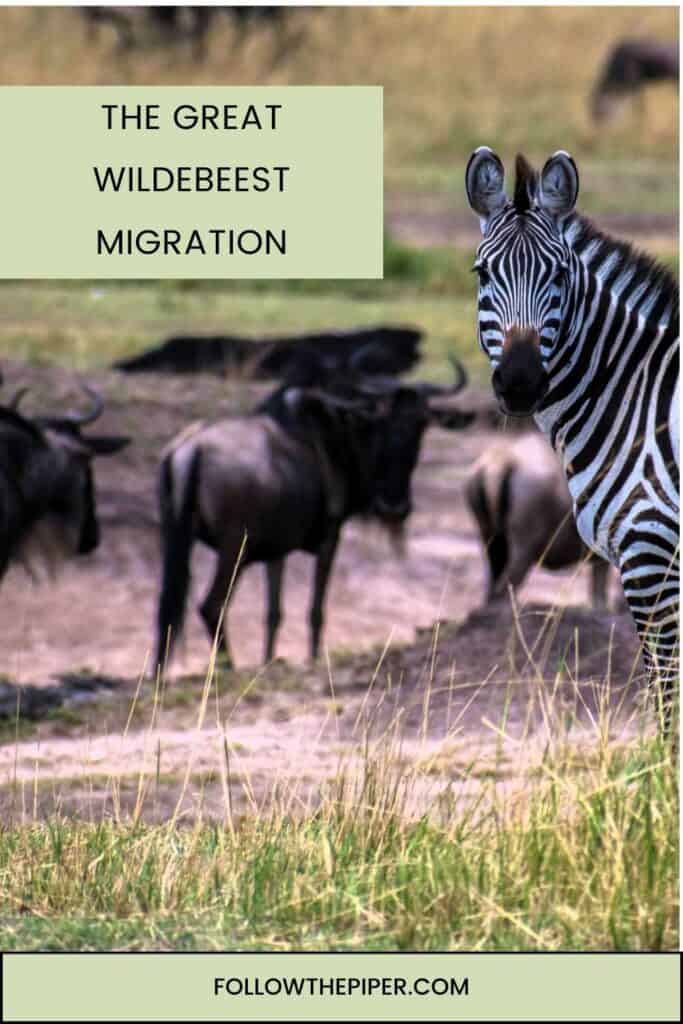

The Great Wildebeest Migration on the Northern Serengeti

I’d come halfway around the planet to Tanzania to witness the Great Wildebeest Migration, but specifically to watch those animals leap from the cliffs of the riverbank into the Mara River, in hopes of capturing some National Geographic-worthy images. As an avid photographer who spends hours waiting for just the right photo shot of my Midwestern wildlife, I’d imagined the thundering hooves, and dreamt of capturing the splash, and maybe even a glimpse of the circle of life. Now I was here! I NEEDED to see it with my own eyes. I wanted to capture that moment, not only in my memory but digitally to share long after I returned home. To remember it forever—every detail.

The travel brochures made no guarantees that I would witness a river crossing. Of course, how could they? The ultimate experience depends on the animals themselves, and I’m sure they haven’t read the brochure, especially the part where they’re supposed to take that mighty leap.

The northern Serengeti is private, isolated, and a challenge to get to. We flew into Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, in the remote Northern Serengeti on a twelve-passenger bush plane. Our pilot circled over the Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano, as we peered into its full mouth. We continued over Lake Natron, the soda lake, where that day, the bright pink flamingos were disappointedly absent.

Finally, as we landed, the mixture of sweat from the heat, the taste of the dry swirling dirt, and arid smells reminded me this wasn’t an excursion to the San Diego zoo.

When is the Best Time to See the Great Wildebeest Migration?

Every year over two million wildebeest make the journey from the northern Serengeti plains to Kenya’s Maasai Mara with over 200,000 zebras and 500,000 Thompson’s gazelles as their traveling companions on their endless journey.

August and September are the best months to witness the migration, as the rainy season begins in October when the herds start their return. The movement is continuous as wildebeest and zebra co-exist together, each eating different parts of the grass. Zebras feast on the long, tough grass while the wildebeest eat the short grass.

With no map, no feeding schedule, no scheduled shows, the excitement builds. What’s next? When will the crossing happen? Where? Which crossing point? Like life, it’s unpredictable. You need to wait. Life isn’t always mapped out. The journey takes unexpected turns.

Waiting to catch a crossing is uncertain as there isn’t a single crossing point. You move from one crossing point to another, trying to be at that one point where the animals have decided to leap. Catching a crossing is unpredictable at best and involves a lot of luck.

The Mara River crossing is a small slice of the migration. Hundreds of wildebeest create a back-up and may push those in the front into the Mara River. The wildebeest and zebra mingle on the riverbank, waiting for a critical mass. Small groups waiting, as there’s safety in numbers.

Dangers lurk unseen below the water’s surface until one brave wildebeest takes that jump into the river, which triggers the mass of hundreds. Thousands of thundering hooves begin the stampede. It’s a small slice, but the most important to my ultimate experience.

Even Frances couldn’t promise we’d have the ultimate experience, but I still hoped, trusted, and believed his knowledge of local animal behavior would increase our luck.

End of Day One

Returning to our luxury glamping camp that evening, was a bit of a letdown. After all, our time was limited. We only had one more day before we departed for the Central Serengeti. Those wildebeest needed to learn cooperation. Right?

Over dinner with long faces, we mulled over our experiences from the day. What images had we captured? One of the three groups had waited and had seen a leap, but for some reason, the group was relatively small. Still disappointing. Our guides discussed the possibilities. Which crossing point held the most promise?

Today, even though we’d raced over a rough road, we’d done our best, gone our fastest, we still had missed them. I came to the far reaches of the Northern Serengeti, flying seven hours to Amsterdam, had a long layover then flew several more hours to Arusha, Tanzania. After an overnight, I’d flown in a 12-passenger bush plane over volcanos and soda lakes, then ridden over the washboard-ridged packed dirt road that resulted in a throbbing tailbone. I came all this way for something I’ve been yearning to witness for years. Tonight, I’m wondering, will I even get to see the infamous leap at all?

Risky Business

The traveling companions can see – the danger – the crocodiles lying in wait, just below the water’s surface. With the sound of thousands of hooves hitting the ground – running – they tend to defer to each other, waiting for a critical mass. Then they might stand a chance against the crocodiles lying in wait, that critical mass and their thousands of hooves might trample those crocodiles instead of becoming prey to them.

While the migration isn’t without hazards, the dangers of crossing the Mara River is especially perilous. Some are weak swimmers and drown under Mara’s swift currents. Other times the group may choose a crossing point that’s too deep, and thousands may drown.

Leaping off the cliff’s edge into the water, perhaps one will break a leg. While clamoring up the slippery, steep embankment, one might fall back into the rest of the herd below, resulting in the injury of several.

Day Two – Waiting

On the second day, our guides stopped at each passing jeep, inquiring what the other guide might have seen or heard. Where were the groups assembling today, they asked? What intel did they have? With more knowledge gained, they made a decision. The guides figured out the spot where we would wait. And wait we did. Quickly time passed as we captured images of the increasing numbers. Wildebeest and zebra numbers continued to increase. The larger the numbers, the longer the crossing will be. We must be patient. The time waiting wasn’t wasted. We captured hundreds of images, and still, we waited.

The wildebeest looks like an assemblage of spare parts put together as a child might build their piece in the children’s game Cootie or Mr. Potato Head. The body of a thin head of cattle, the beard of a goat, a horse’s tail, and horns of a water buffalo all combined to create the beast referred to as the wildebeest.

Watch Out for Danger

Predators add to the danger. Nile crocodiles’ strong jaws wait for wildebeest and zebras as their next meal. They know it’s coming, is just a question of when. Hippos protect their territory from the intrusion, while hyenas and lions lay in wait, knowing this is a vulnerable time for the wildebeest and zebras.

Over 250,000 wildebeest die annually during their migration, from predators, injuries, stampedes, or drowning.

Young and inexperienced, the youth crossing poses another set of problems. Watching the passage of young wildebeests and zebras across the river is not for observers of the faint of heart.

Some wildebeest youth made it across the Mara yet turned around to go back. Separated from their family, and inexperience, he panicked and returned to the starting point. Frantically he searched for his group.

The youth’s legs may be as short as a footstool’s, making the climb up the steep rocky slope impossible, forcing them to return to the crocodile-infested waters in search of an alternate path–looking for one that’s less steep and more approachable.

Zebras edge toward the bank to assist without getting too close. Sometimes adults come to the water’s edge to help the youths; other times, they don’t make it.

The Ultimate Great Wildebeest Migration Experience

Over an hour had passed. The numbers were getting higher, so many that all we could see were wildebeest and zebras. With our Land Rover parked on the opposite side of the river where we’d hope they would jump, we waited. We were ready with our telephoto lens when the first brave soul leaped.

Then, suddenly it happened. Not as expected, but instead, the zebra and wildebeest walked down the grassy slope, and with no need to leap, they walked into the water for a safer descent. While the water splashed as expected, as we made some excellent images of the splash, the wildebeest had picked their spot wisely, so they didn’t need to leap, reducing the threat of a broken leg.

The Unexpected

Yet, this was still the ultimate experience in an unexpected way. Our Land Rover sat in precisely the spot the wildebeest chose to ascend. Coming up out of the river, on the opposite side, seemed more difficult than I expected. I had always imagined the beginning, but the surprise was the end. You could see in their faces the exertion required to make it up the bank. Running to make the final steps and get out of the way before the rest of the troops ran them over. Like the splash at the beginning, mud flew everywhere as they shook it off, like a dog after a bath.

After two days, on the Northern Serengeti, yes, I agree with Frances; this wildebeest migration is a crazy business. You can approach it in one of two ways. You can sit and wait for them to cross patiently, or you can rush from one point to the next and hope to be at the right place at the right time. Patience, hope, and a bit of luck are what it takes.

Find some vacation planning tips, for planning your next adventure, in my post 7 Ways to Pack More Relaxing Travel in Your Over-Scheduled Life.

Pin this for later!

While Piper is a lifelong Michigander, she’s had adventures worldwide. Bomb-sniffing dogs chased her in the middle of the night in Bogota (working late), gate agents refused her boarding to Paraguay (wrong visa), and US Marshals announced her seat number on a plane while looking for a murder suspect (she’d traded seats). It’s always an adventure! She even finds exciting activities in her home state of Michigan, where she lives in Lansing with her husband, Ross Dingman, her daughter, Alexis, and two granddaughters.

Was very interesting how you TRAVELed on your trip. Your description of the rough roads kind of reminded me of the Nixon road Dick and Pearl live on.only not as bad as those you were on. Lol Captures one’s imagine and expectations of what may happen each day. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and experiences. Well written!

Thank you! Believe me this was much, much worse than Nixon Road though. At some points it seemed to be a cow path. And when the guides were saying we needed to stay on the road, I literally thought what road? All of that said, it was the experience of a lifetime!

What an amazing experience this must be to see in person! I’ve been on safari and have seen these animals in person but never a migration. Thanks for sharing!

This is definitely a trip i’d love to take! The photos are amazing and it sounds so exciting.

What an amazing trip. I’d love to go on safari and see all these amazing animals.

I’m glad you got to see the Wildebeest Cross! Sounds like an incredible trip!